From Rage to Righteousness: Learning to Steward Holy Anger

Let's take a quick history pop quiz. See if you can guess the world leader…

Even before he rose to power, this man was known for stretching the truth about his military accomplishments in combat.While president, the gap between the wealthiest and poorest in his country widened. For two decades, he used the power of his office to rob his country's coffers and enrich his family and his cronies. Authoritarian in style, this leader ordered his military to take over privately owned media outlets that he accused of being Communist. His main political rival was imprisoned and later assassinated, and activists and critics of his administration were arrested, tortured, and sometimes killed. The economy of his country suffered while he was in office, as it experienced a debt crisis and the loss of two decades of economic development.

Perhaps several names come to mind as you read the above description. If you guessed President Ferdinand Marcos of the Philippines, you've passed this quiz!

In the 2019 documentary The Kingmaker, Director Lauren Greenfield spotlights Marcos' widow, Imelda Marcos, who presents a revisionist version of her late husband's controversial legacy. Imelda is perhaps most widely known for her extensive shoe collection (3,000 by the government and media's count, 1,000 by Imelda's count). Footage of Imelda handing out peso banknotes to the poor Filipinos she comes across as she travels through town stands in stark contrast to the reality of the billions that Marcos plundered from the Philippine treasury. (Estimates are around $10 billion, and the amount could be even higher because of accumulated interest on those assets.)

In an incredible moment in the documentary, Imelda openly tells the filmmaker: "Perception is real, and the truth is not."

She also drops this line: "I have money in 170 banks."

I recently watched The Kingmaker for the first time and felt a mix of emotions: Curiosity, for sure, because my knowledge of Philippine history, even as a Filipino American, is still so woefully inadequate. But I also felt anger and grief. Images of shanty towns and malnourished children from my previous trips to the Philippines flashed through my mind. More than 15% of Filipinos live below the poverty line, and many of those above the poverty line work long hours for paltry wages; meanwhile, unchecked corruption in the Philippine government runs rampant, and families like the Marcoses reside in gilded mansions.

I was born in the Philippines the year after Ferdinand Marcos' death, and my family was eager to leave the corruption of our homeland that lingered long after Marcos' 20 years in office (including when he enacted martial law, he ruled from 1965-1986, before he was exiled to Hawaii). My parents and I immigrated to Southern California when I was 2, and every time I asked my parents why we left, the answer was the same: to escape the corrupt government in the Philippines.

Essentially, Marcos' greed and plundering of my homeland directly led to my family seeking refuge and a better life in America.

To add a few layers to my grief and anger: Since the documentary came out, Marcos' son, Ferdinand "Bongbong" Marcos Jr., has been elected president of the Philippines. It is all but guaranteed that the money his parents and their allies stole from the Filipino people will remain in the Marcos' many bank accounts. And the efforts to rewrite Ferdinand Marcos Sr.'s legacy continue on, this time from the sitting Philippine president.

My journey to learn more about the history of my motherland has been enlightening – and infuriating. Marcos' now-grown children are current Philippine politicians. They've been urging the Filipino people to forgive and forget. At the same time, they refuse to be held accountable for the $10 billion stolen from their people and continue to deny the lengthy list of human rights violations, including 3,257 (known) extrajudicial killings during the Marcos regime.

My anger at these abuses and the continued disinformation campaign to rewrite Marcos' legacy can often get the best of me. As injustices continue in our world and country today, I've had to ask myself these questions: How should we handle the anger we feel at such injustices? What is a spiritually mature response to such anger?

"Be angry, and sin not."

In Ephesians, as Paul describes the new self that's created after the likeness of God, he admonishes, "In your anger do not sin" (Eph. 4:26 NIV). As someone raised in a fundamentalist Christian space that discouraged women from ever expressing anger, I find it a relief to know that feeling angry itself is not sinful. But left unchecked, anger can so easily slip into resentment, bitterness, hatred, and malice.

Scripture gives several accounts of Jesus experiencing anger, and the one that always comes to mind for me is during the cleansing of the temple courts. It was nearly time for Passover, and Jesus went up to Jerusalem, where he came across people exchanging money for the temple tax and selling animals for sacrifice. Undoubtedly, some of these transactions exploited the poor, who were overcharged for the pigeons and doves they sought to purchase. All of this was happening in the court of the Gentiles, which would've been the closest any non-Jew could get to the sanctuary.

John's account of this story tells us that Jesus made a whip of cords, drove out the animals from the temple courts, scattered the coins of the money changers, and overturned their tables. "Get these out of here! Stop turning my Father's house into a market!" (John 2:16 NIV). You can feel his indignation at the injustice toward the poor pilgrims seeking to offer sacrifice and the Gentile believers whose one designated place of worship in the temple was crowded out by commerce.

What a relief that our High Priest is able to empathize with our weaknesses, as Hebrews reminds us, including our propensity toward anger! In his anger, his actions at the temple were not reactionary but deliberate, not driven by selfish motivations but rather by grief at the way the poor were being exploited and the outcasts were being further excluded from God's presence. His anger also never turned violent toward others. In this story, we have a model from Jesus of how to "be angry and sin not."

Going beneath the surface

In addition to looking at how Jesus experienced and expressed anger, it's beneficial to see what those who study human emotions have to say as well.

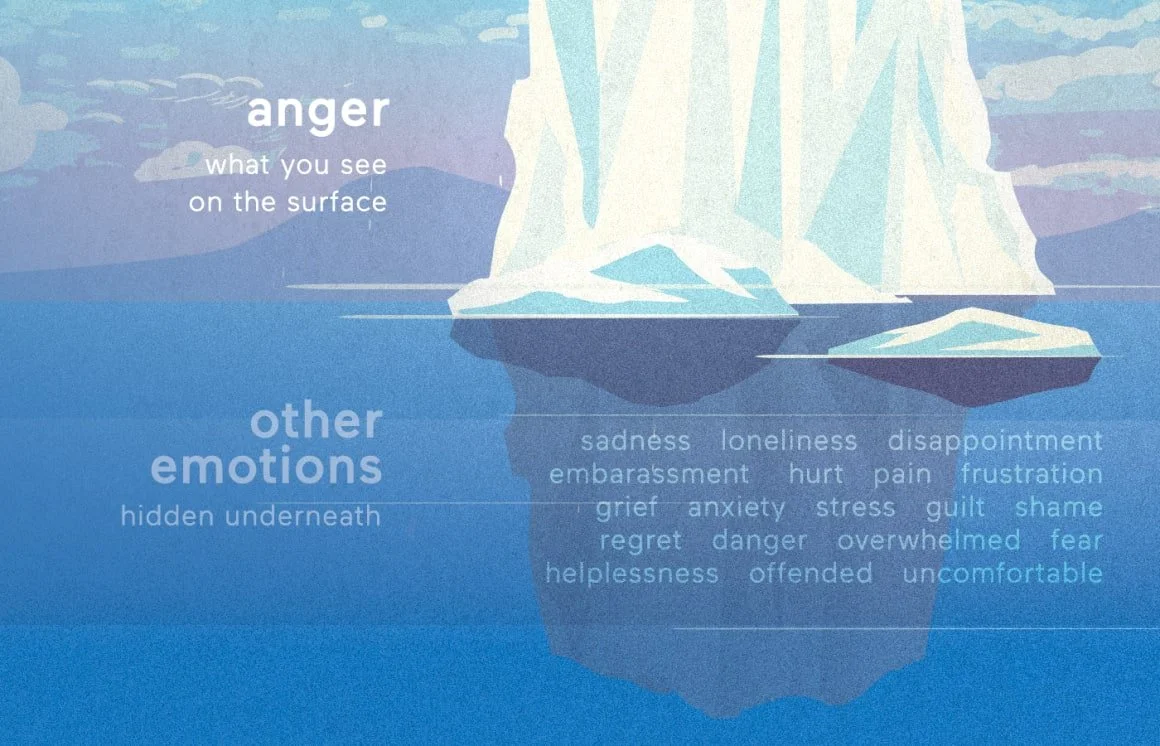

Psychologists tell us that anger is a valid primary emotion, but it often is a secondary emotion as well, masking other emotions such as fear, sadness, etc. This concept is illustrated through the Anger Iceberg theory, created by The Gottman Institute. Like seeing the tip of an iceberg, it can be easy to see someone's anger and much more difficult to see below the surface, the underlying raw feelings that anger is protecting.

(Source: https://mindbodygreen-res.cloudinary.com/image/upload/w_580,q_auto,f_auto,fl_lossy/dpr_2.0/org/nw2s1olywkblk7stt.jpg)

When we experience anger, a helpful practice can be to take a beat and reflect. Is there an underlying emotion(s) to this anger? Try your best to identify them. Is this anger ultimately protecting fear, grief, or powerlessness? For me, many times, my anger is protecting grief over the brokenness I see in our world and my perceived powerlessness to do anything about it.

In a recent interview with Russell Moore in Christianity Today, NYC Pastor and Author Rich Villodas shared some important insights on anger. "Lament—naming what's beneath the anger and lifting that to God—can be a significant pathway to getting to the core of what our anger is revealing. Anger is usually secondary and symptomatic of something deeper. And God can handle it."

Anger as a "Side B" Christian

For those of us who experience same-sex attraction and/or gender dysphoria and hold to the Church's view of traditional marriage, anger can pop up for any number of reasons. "Side B" Christians have experienced the loss of jobs and income due to their being honest about their lived experience with sexuality/gender. We have lost ministry positions, friendships in the Church, and relational ties with family members… we've faced suspicion and scrutiny over our interactions with others… on and on. I know I have had to guard my anger over such situations from slipping into bitterness.

To my "Side B" siblings: your anger over these types of situations is valid. I encourage you to bring your full experience of anger to Jesus. He stands in solidarity with you and wants to hear your heart.

To "Side B" allies, I ask: will you step into these feelings of anger with us? Will you speak up when your "Side B" friends face injustice within the Church and metaphorically flip some tables when sexual minorities are further prevented from drawing closer to God?

"Outrage is a signal to speak up." – Adam Grant, organizational psychologist and author.

Just as anger led Jesus to speak up and take action in the temple, so too can our anger be a catalyst for advocacy and positive action.

Christian Author Sarah Bessey recently wrote in her Substack newsletter, "Our soul-centered anger is a gift, a powerful force we can steward with care and intention as we rise up at injustice." (Bessey's post on anger was published after I decided to write this blog post, and she articulates so well what I attempted to do here. I cannot recommend it highly enough.)

Bessey urges her readers to pay attention to their anger and learn to steward it well as an invitation from God. To consider that "the Holy Spirit is active in that space of righteous anger."

I see parallels in the ancient Ignatian spirituality exercises like the Examen that call for an awareness of one's emotions and then discernment of one's source and what God is trying to say through that emotion (and, further, how we are to respond).

As we experience anger and identify the underlying feelings, let's consider: what is the Holy Spirit prompting me to do? Is there a conversation I need to have with someone, an email, or a call to an elected official I need to make?

On the flip side, if there's very little that causes you to experience anger, I invite you to reflect on why that might be. Christ never called us to ignore our anger. A lack of anger, or indifference toward others' suffering and experiences of injustice, seems to be the exact opposite of what Isaiah 1:17 commands:

"Learn to do right; seek justice.

Defend the oppressed.

Take up the cause of the fatherless;

plead the case of the widow."

If we take seriously the command to love our neighbor, seeking justice for our neighbor must be part of our modus operandi. "Justice is what love looks like in public," as Dr. Cornel West said.

Anger is insufficient fuel.

The relationship between the fight for justice and love has been touched on before on this blog, most recently in Johana-Marie Williams' post on "Cultivating Agapic Energy." I appreciated learning about "agapic energy" and the reminder to re-center on love, as "love is the core of resistance and resilience, the core of tearing down idolatries and building up communities."

It's been about a decade, but I've run a couple of marathons in my life. One thing I learned the hard way while training was that the food I consumed directly contributed to my ability to run well (or not). Some foods simply didn't cut it asproper sustenance for the next day's training run.

The same goes for anger and the fight for justice. Anger can be the flash point for action but will be insufficient fuel for the long haul. To quote Bessey's post again, "Anger is our holy starting point, sure, but it is Love who sustains the passion and directs it into life-giving transformation." The fight for justice ever remains a marathon, not a sprint, and we need sustainable fuel if we want to finish the race well.

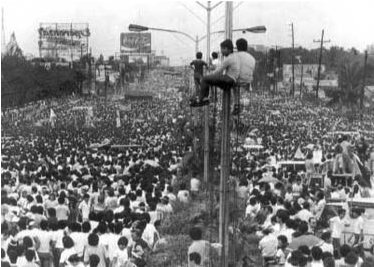

Hundreds of thousands of Filipinos filled the streets in February 1986 for three days in a nonviolent protest, which led to Ferdinand Marcos Sr.’s departure and the end of his 20-year dictatorship.